Coal seam gas, or clean drinking water. It can’t be both

October 23, 2014

“Drop-a-brick” – Water Conservation

October 23, 2014I love reading about all sorts of scientific discoveries, and this makes for an amazing one!

Scientists have managed to sequence the genome of a 45,000 year old bone and thereby discovered when modern humans and Neanderthals interbred, right down to a 10,000 year window!

Isn’t that amazing?!

He lived about 45,000 years ago and died on the banks of a river in Siberia and now scientists have decoded his DNA to narrow the time when humans and Neanderthals first got a little bit frisky.

The individual, named Ust’-Ishim man after the settlement close to his burial site, represents the earliest modern human outside Africa to have their genome sequenced.

An international team of geneticists, led by ancient DNA specialist Svante Paabo from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, extracted DNA from the man’s thigh bone.

Neanderthals and modern humans likely interbred between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago.

The team used radio carbon dating to established the bone was about 45,000 years old.

The man’s genetic blueprint suggests he came from a population of ancient humans that lived before, or with, the population of Eurasians that separated into western and eastern groups.

The man’s genes also narrow the date when modern humans and Neanderthals interbred to between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago.

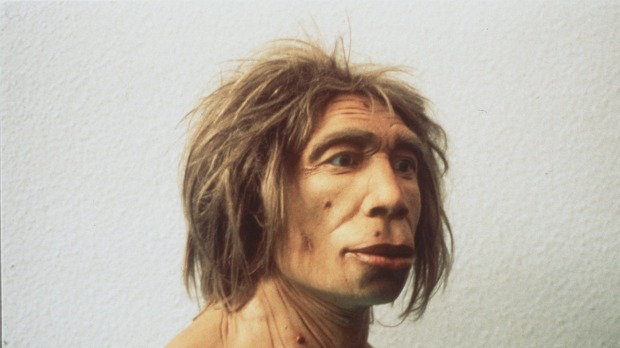

Geneticists extracted DNA from the thigh bone of Ust’-Ishim man, who lived 45,000 years ago. Photo: Bence Viola

Based on the genomes of living people, researchers have previously estimated modern humans and Neanderthals interbred between 36,000 and 80,000 years ago.

“This new sequence proves it was at least 6000 years prior to that,” said Jeremy Austin, an ancient DNA researcher from the University of Adelaide, who was not involved with the research.

He said sequencing ancient DNA allowed scientists to peer back in time and observe breeding events as they happened, rather than infer what may have happened based on the genomes of contemporary humans.

While the Ust’-Ishim man carried a similar amount of Neanderthal DNA as contemporary Eurasians, his were packaged in longer segments.

As genetic information is passed from one generation to another segments of DNA break up and recombine, which meant younger Eurasians would have shorter sections of Neanderthal DNA.

“The closer you get to that interbreeding time period the longer the Neanderthal pieces of chromosomes become,” said Dr Austin, the deputy director of the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, at the University of Adelaide.

The results also provide insights into migration patterns as early humans moved out of Africa and across central Asia.

Dr Austin said one theory suggested that an early coastal migration from African gave rise to people now living in Oceania. And a later second wave of people from Africa gave rise to Europeans and mainland Asians.

But the existence of a 45,000-year-old man from Siberia, who is not more closely related to the descendants of either group, suggests there may have been another group that migrated through central and east Asia, said the research team.

Their findings have been published in the journal Nature.